“The potatoes there are so much better…Here the chicken tastes different,” says one of the characters in Oswaldo Estrada’s Dreams in Times of War. His words aptly bring to light the displacement experienced by immigrants, of that shaky ground of here and there, which is the inevitable result of leaving one’s country in search of a new home. The twelve short stories in this bilingual collection offer a myriad of experiences and voices of Latin American immigrants, showcasing the diversity of the so-called “Latine community” in the United States. They narrate the lives of immigrants as waiters, students, tobacco workers, nannies, professors, gardeners and teachers from Mexico, Central and South America. Estrada’s complex characters are marked by loss, violence, and trauma, but also by hope, camaraderie and dreams.

In the opening story, which gives the collection its title, “Dreams in Times of War,” Estrada invites us into a narrative space marked by multiplicity. The protagonist is a young Peruvian American born in the U.S who is brought back to Perú by his parents at a young age. He grows up amid the violence of the war, and a precarious economic situation exacerbated by an absent father. In this challenging scenario, the United States appears as a conflicted space. On the one hand, it is a place that offers a “safe conduct out of this inferno” in the collective imagination (2), a place where one can eat pizza at a street corner, ride a yellow school bus, and visit Disneyland. However, as his mother previously experienced, it is also a place of social isolation and hard work. She still wonders if their lives would have been more independent there, if only she “would’ve been more daring” (4). The lives of migrants are anchored in desires and the infinite possibilities of an existence that challenges stable notions of identity and belonging. For Estrada’s characters, being at war is not only the consequence of experiencing an armed conflict, but a metaphor for displacement.

The immigrant bodies become territories marked by different forms of violence. In “Under My Skin,” for example, we follow a single mother and her daughter who are migrant tobacco field workers perpetually moving across the U.S. to follow the harvest seasons. The daughter struggles with the constant moving and she wonders how their lives would have been different had they stayed in Mexico. Her mother frequently falls ill from contact with an invisible and odorless toxic substance in the tobacco leaves invading the workers’ bodies like “a green monster that spreads under the skin. With tentacles that poison every part of you.” Despite this danger, they—like many other workers—keep returning to work every year, “As if our bodies were addicted to these fields…because the gringo pays well” (39-40). In “Assisted Living,” we meet Mariana, who endures insults, aggressions and difficult cleaning tasks from the senior residents of the assisted living facility where she works. She “doesn’t complain about her back pain or her feet…” or the scratches left on her skin by the residents, and she saves every penny in hopes of reuniting with her daughter (25-27). With a prose that oscillates between harsh reality and intimate reflection, Estrada foregrounds the hardships of working in the U.S. and their impact on the physical and mental health of workers and their families.

Illness is also a symptom of trauma and violent living conditions. War, domestic violence, rape and sexual discrimination leave deep marks on the bodies of immigrants who populate Dreams in Times of War. We meet characters born with asthma whose symptoms reappear as a consequence of settling in a place different from home—an action that threatens to erase nostalgia and the remembrance of origin; a journalism professor researching protests in Latin America who struggles with insomnia; a shy college student who drinks a sip of Benadryl every night to sleep and conceal the trauma of crossing the border. The immigrant body is a site of stories, memories, and the embodied experience of internal conflict: living here while constantly remembering there.

Popular culture and friendships provide an outlet for the challenges of living in a present heavily shaped by the past. For immigrants, watching telenovelas and cooking traditional dishes while listening and dancing to music from their countries rebuilds a sense of home, even if it is just a recreation where “the chicken tastes different and the potatoes are not as good.” Estrada’s characters remind us that “getting together with others who suffered from the same illness” (34) is a way of mitigating the violence of being an Other in search of existential meaning in a reality marked by displacement. At a time when the dominant U.S narrative about immigrants and immigration is one of dehumanization, Dreams in Times of War offers readers a powerful counterpoint: each story reveals the profound and complex ties between Latin America and the United States, as well as the nuanced humanity at the heart of every immigrant experience.

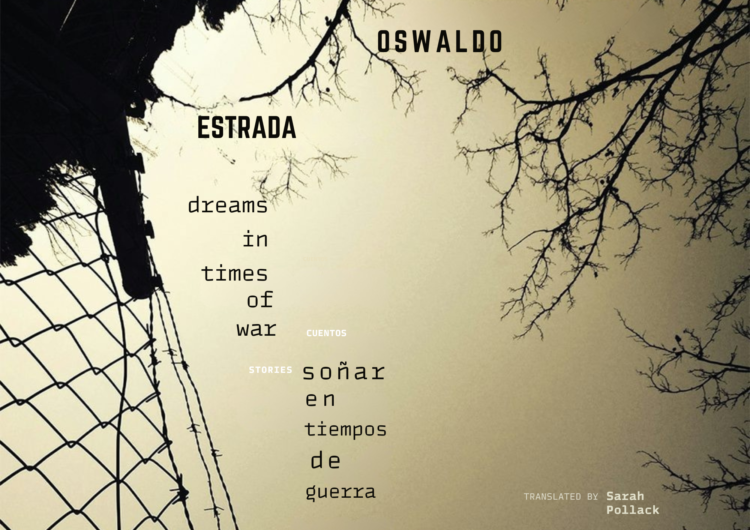

Estrada, Oswaldo. Dreams in Times of War / Soñar en tiempos de guerra. Translated by Sarah Pollack. U of New Mexico P, 2025, 192pp.

Book Author

Oswaldo Estrada is a fiction writer and literary critic. He has authored numerous works, including a children’s book, four collections of short stories, and the novel Tus pequeñas huellas (2023). His book Las guerras perdidas (2021) won the 2022 International Latino Book Award Gold Medal for “Best Collection of Short Stories in Spanish.”

Book Review by

Mayra Fortes González is Associate Professor of Hispanic Literatures and Cultures at Grand Valley State University. She has authored articles on contemporary Latin American literature, counterculture, and the New Latino Boom. She is also co-editor of the edited volume, Ensayando el ensayo. Artilugios del género en el ensayo mexicano contemporáneo (2012).